Wakanda Had to Make Up a State Doesnt Exist Black Panther Review

The Revolutionary

Ability of Blackness Panther

The first flick I remember seeing in a theater had a black hero. Lando Calrissian, played past Billy Dee Williams, didn't have any superpowers, but he ran his own city. That film, the 1980 Star Wars sequel The Empire Strikes Dorsum, introduced Calrissian as a complicated human being existence who still did the right thing. That's one reason I grew up knowing I could be the same.

If you are reading this and you are white, seeing people who look like you in mass media probably isn't something you think about often. Every day, the civilization reflects non only you but about space versions of you—executives, poets, garbage collectors, soldiers, nurses and then on. The world shows yous that your possibilities are dizzying. Now, after a brief respite, you again take a President.

Those of us who are not white take considerably more than problem not only finding representation of ourselves in mass media and other arenas of public life, only also finding representation that indicates that our humanity is multifaceted. Relating to characters onscreen is necessary not merely for united states of america to feel seen and understood, but also for others who need to see and sympathize u.s.. When it doesn't happen, nosotros are all the poorer for it.

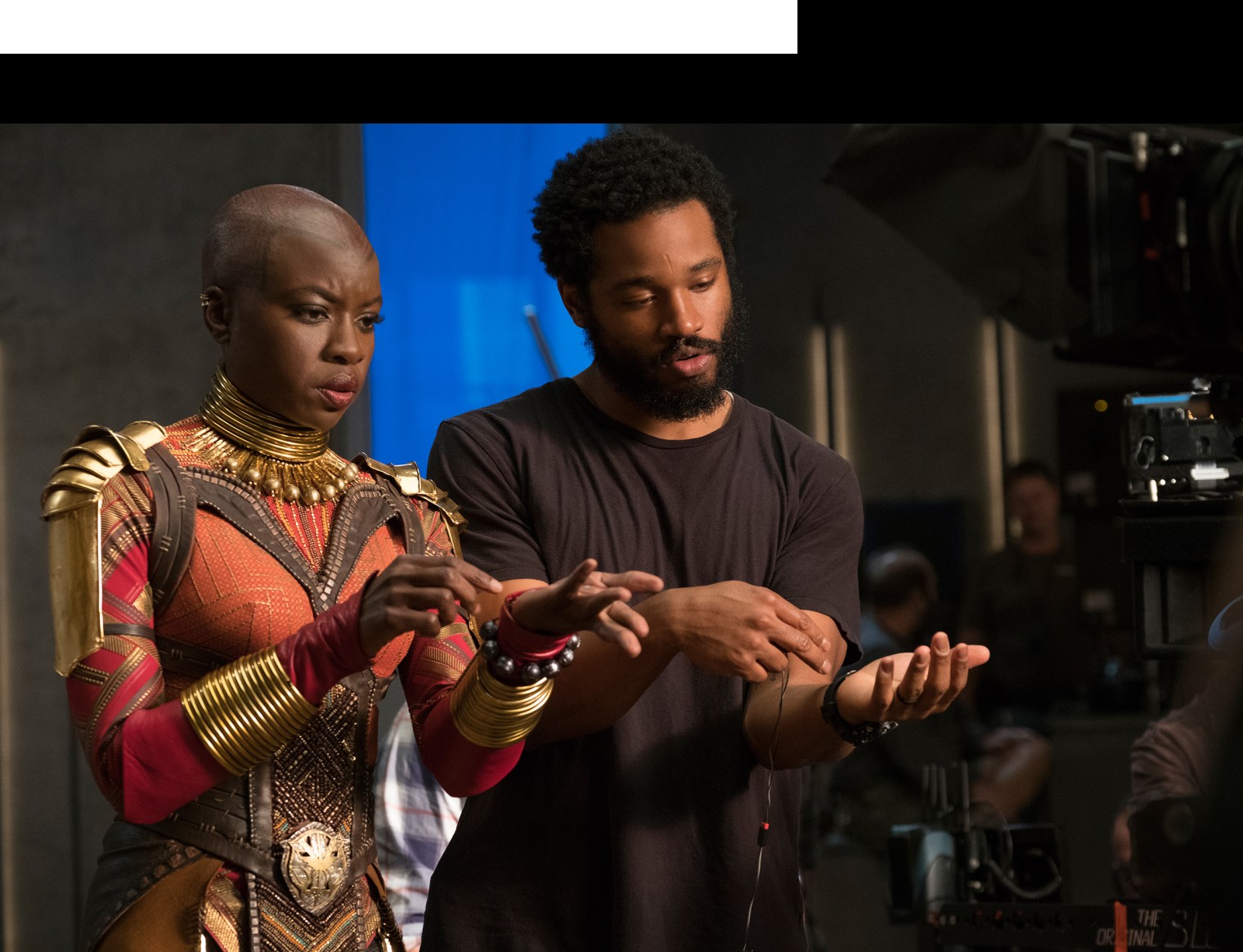

This is one of the many reasons Black Panther is significant. What seems like but another entry in an endless parade of superhero movies is actually something much bigger. It hasn't even hit theaters yet and its cultural footprint is already enormous. It'south a movie virtually what information technology means to exist blackness in both America and Africa—and, more than broadly, in the globe. Rather than dodge complicated themes virtually race and identity, the moving-picture show grapples head-on with the problems affecting modern-day black life. It is likewise incredibly entertaining, filled with timely comedy, sharply choreographed action and gorgeously lit people of all colors. "You have superhero films that are gritty dramas or action comedies," director Ryan Coogler tells TIME. Just this motion-picture show, he says, tackles another of import genre: "Superhero films that deal with issues of beingness of African descent."

Black Panther is the 18th motion-picture show in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, a franchise that has made $13.5 billion at the global box office over the by 10 years. (Marvel is owned by Disney.) It may be the beginning megabudget movie—not just almost superheroes, but well-nigh anyone—to have an African-American director and a predominantly black cast. Hollywood has never produced a blockbuster this splendidly black.

The motion-picture show, out Feb. sixteen, comes as the entertainment industry is wrestling with its toxic treatment of women and persons of color. This speedily expanding reckoning—1 that reflects the importance of representation in our culture—is long overdue. Black Panther is poised to prove to Hollywood that African-American narratives have the ability to generate profits from all audiences. And, more of import, that making movies virtually blackness lives is office of showing that they affair.

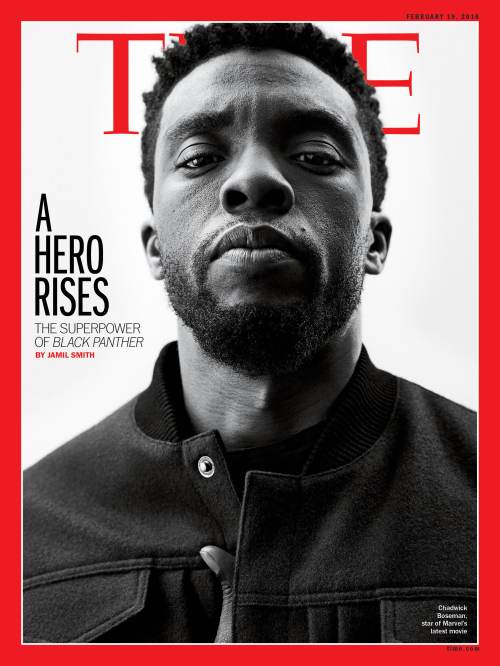

The invitation to the Black Panther premiere read "Royal attire requested." Yet no one showed upwards to the Dolby Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard on Jan. 29 looking like an extra from a British costume drama. On display instead were crowns of a dissimilar sort—ascending caput wraps made of diverse African fabrics. Oscar winner Lupita Nyong'o wore her natural hair tightly wrapped above a resplendent bejeweled imperial gown. Men, including star Chadwick Boseman and Coogler, wore Afrocentric patterns and clothing, dashikis and boubous. Co-star Daniel Kaluuya, an Oscar nominee for his star turn in Go out, arrived wearing a kanzu, the formal tunic of his Ugandan ancestry.

After the Obama era, perhaps none of this should feel groundbreaking. Only it does. In the midst of a regressive cultural and political moment fueled in part by the white-nativist motility, the very existence of Blackness Panther feels like resistance. Its themes claiming institutional bias, its characters have unsubtle digs at oppressors, and its narrative includes prismatic perspectives on black life and tradition. The fact that Black Panther is excellent only helps.

Back when the film was announced, in 2014, nobody knew that it would be released into the fraught climate of President Trump's America—where a thriving black future seems more than hard to see. Trump'south reaction to the Charlottesville chaos concluding summer equated those protesting racism with violent neo-Nazis defending a statue honoring a Confederate general. Immigrants from Mexico, Central America and predominantly Muslim countries are some of the President'due south nearly frequent scapegoats. So what does it hateful to see this film, a vision of unmitigated blackness excellence, in a moment when the Commander in Primary reportedly, in a recent meeting, dismissed the 54 nations of Africa every bit "sh-thole countries"?

As is typical of the climate we're in, Black Panther is already running into its share of trolls—including a Facebook group that sought, unsuccessfully, to alluvion the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes with negative ratings of the picture show. That Black Panther signifies a threat to some is unsurprising. A fictional African Rex with the technological war power to destroy you—or, worse, the wealth to buy your country—may not please someone who just wants to consume the latest Marvel chapter without deeper political consideration. Black Panther is emblematic of the most productive responses to bigotry: rather than going for hearts and minds of racists, it celebrates what those who choose to prohibit equal representation and rights are ignoring, willfully or not. They are missing out on the full possibility of the globe and the very America they seek to brand "great." They cannot stop this representation of it. When because the folks who preemptively hate Black Panther and seek to terminate information technology from influencing American civilization, I echo the response that the picture's hero T'Challa is known to give when warned of those who seek to invade his home land: Allow them try.

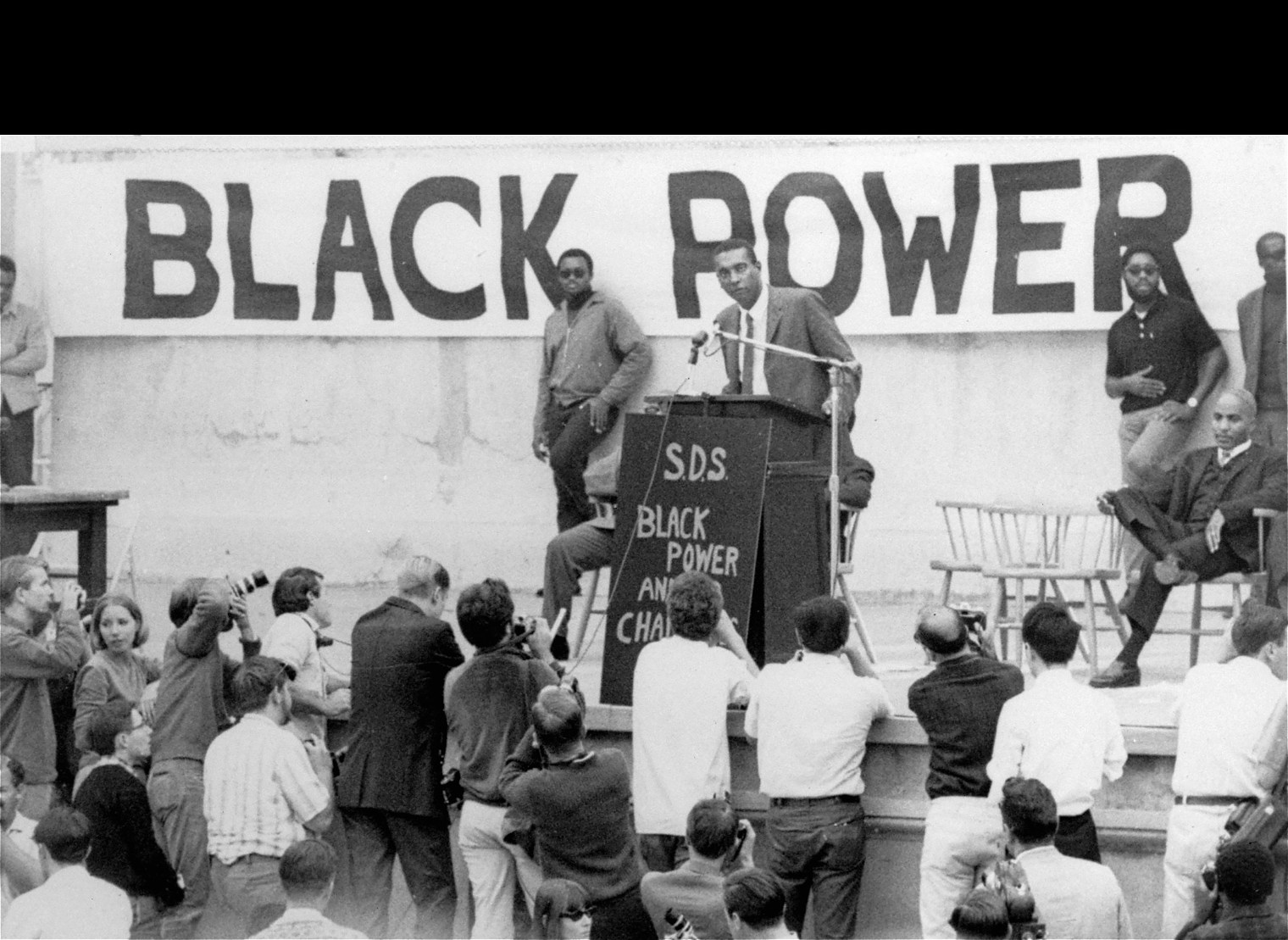

The history of black power and the movement that diameter its name can be traced back to the summertime of 1966. The activist Stokely Carmichael was searching for something more than than mere freedom. To him, integration in a white-dominated America meant absorption by default. About one yr after the bump-off of Malcolm 10 and the Watts riots in Los Angeles, Carmichael took over the Pupil Nonviolent Analogous Committee from John Lewis. Carmichael decided to motion the organization abroad from a philosophy of pacifism and escalate the group'south militancy to emphasize armed self-defense, black business buying and community command.

In June of that yr, James Meredith, an activist who four years earlier had become the first black person admitted to Ole Miss, started the March Confronting Fear, a long walk of protest from Memphis to Mississippi, alone. On the second day of the march, he was wounded by a gunman. Carmichael and tens of thousands of others continued in Meredith's absence. Carmichael, who was arrested halfway through the march, was incensed upon his release. "The but way we gonna cease them white men from whuppin' us is to take over," he declared earlier a passionate oversupply on June sixteen. "We been saying freedom for half-dozen years and we ain't got nothin'. What we gonna start sayin' now is Black Power!"

Blackness Panther was born in the civil rights era, and he reflected the politics of that time. The month after Carmichael's Black Power announcement, the grapheme debuted in Curiosity Comics' Fantastic Four No. 52. Supernatural strength and agility were his primary features, only a genius intellect was his best attribute. "Black Panther" wasn't an change ego; it was the formal championship for T'Challa, Male monarch of Wakanda, a fictional African nation that, cheers to its exclusive agree on the sound-absorptive metallic vibranium, had become the almost technologically advanced nation in the world.

Information technology was a vision of black grandeur and, indeed, ability in a trying time, when more than than 41% of African Americans were at or below the poverty line and comprised nigh a third of the nation's poor. Much like the iconic Lieutenant Uhura character, played past Nichelle Nichols, that debuted in Star Expedition in September 1966, Blackness Panther was an expression of Afrofuturism—an ethos that fuses African mythologies, engineering science and science fiction and serves to rebuke conventional depictions of (or, worse, efforts to bring nigh) a hereafter insufficient of black people. His white creators, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, did non consciously conjure a fantasy-world response to Carmichael's phone call, just the image nonetheless held power. T'Challa was not only strong and educated; he was also royalty. He didn't have to take over. He was already in charge.

"You might say that this African nation is fantasy," says Boseman, who portrays T'Challa in the movie. "But to have the opportunity to pull from existent ideas, real places and real African concepts, and put it inside of this idea of Wakanda—that's a great opportunity to develop a sense of what that identity is, especially when you're asunder from it."

The character emerged at a time when the civil rights movement rightfully began to increase its demands of an America that had promised so much and delivered so little to its black population. Fifty-2 years after the introduction of T'Challa, those demands take yet to be fully answered. According to the Federal Reserve, the typical African-American family unit had a median cyberspace worth of $17,600 in 2016. In contrast, white households had a median net worth of $171,000. The revolutionary affair nigh Black Panther is that it envisions a world non devoid of racism but ane in which black people have the wealth, technology and armed services might to level the playing field—a scenario applicative not only to the predominantly white landscape of Hollywood but, more of import, to the world at large.

The Black Panther Party, the revolutionary organization founded in Oakland, Calif., a few months after T'Challa'due south debut, was depicted in the media as a threatening and radical grouping with goals that differed dramatically from the more pacifist vision of civil rights leaders similar Martin Luther King Jr. and Lewis. Marvel fifty-fifty briefly changed the graphic symbol's proper noun to Black Leopard because of the inevitable association with the Panthers, but soon reverted. For some viewers, "Blackness Panther" may take undeservedly sinister connotations, only the 2018 picture show reclaims the symbol to be celebrated by all every bit an avatar for modify.

The urgency for change is partly what Carmichael was trying to express in the summertime of '66, and the powers that be needed to listen. It's still truthful in 2018.

Moviegoers first encountered Boseman's T'Challa in Curiosity's 2016 ensemble hit Helm America: Civil War, and he instantly cutting a hitting figure in his sleek vibranium suit. As Black Panther opens, with T'Challa grieving the decease of his male parent and coming to grips with his sudden rise to the Wakandan throne, it's articulate that our hero'south imperial upbringing has kept him sheltered from the realities of how systemic racism has touched merely about every blackness life across the globe.

The comic, especially in its about recent incarnations equally rendered past the writers Ta-Nehisi Coates and Roxane Gay, has worked to expunge Eurocentric misconceptions of Africa—and the film's imagery and thematic material follow suit. "People often inquire, 'What is Black Panther? What is his power?' And they have a misconception that he merely has power through his suit," says Boseman. "The character is existing with power within power."

Coogler says that Blackness Panther, like his previous films—including the police-brutality drama Fruitvale Station and his innovative Rocky sequel Creed—explores issues of identity. "That's something I've ever struggled with as a person," says the director. "Like the kickoff time that I establish out I was black." He's talking less most an epidermal cocky-awareness than about learning how white society views his black skin. "Not only identity, just names. 'Who are you lot?' is a question that comes up a lot in this movie. T'Challa knows exactly who he is. The antagonist in this film has many names."

That villain comes in the class of Erik "Killmonger" Stevens, a one-time blackness-ops soldier with Wakandan ties who seeks to both outwit and trounce downwards T'Challa for the crown. As played by a scene-stealing Michael B. Hashemite kingdom of jordan, Killmonger'due south motivations illuminate thorny questions about how blackness people worldwide should best utilize their power.

In the moving picture, Killmonger is, like Coogler, a native of Oakland. By exploring the disparate experiences of Africans and African Americans, Coogler shines a vivid light on the psychic scars of slavery's legacy and how black Americans endure the existent-life consequences of it in the nowadays day. Killmonger'south perspective is rendered in total; his rage over how he and other blackness people across the world accept been disenfranchised and disempowered is justifiable.

Coogler, who co-wrote the screenplay with Joe Robert Cole, also includes another important antagonist from the comics: the dastardly and narrow-minded Ulysses Klaue (Andy Serkis). "What I love about this experience is that it could have been the thought of black exploitation: he's gonna fight Klaue, he's gonna go after the white man and that's it—that's the enemy," Boseman says. He recognizes that some fans will take issue with a black male villain fighting black protagonists. Killmonger fights not merely T'Challa, but likewise warrior women like the spy Nakia (Nyong'o), Okoye (Danai Gurira) and the rest of the Dora Milaje, T'Challa's all-female royal guards. Killmonger and Shuri (Letitia Wright), T'Challa's quippy tech-genius sister, besides face up off.

T'Challa and Killmonger are mirror images, separated just by the blow of where they were built-in. "What they don't realize," Boseman says, "is that the greatest conflict you will ever face will be the conflict with yourself."

Both T'Challa and Killmonger had to be compelling in order for the picture show to succeed. "Obviously, the superhero is who puts you in the seat," Coogler says.

"That's who you want to meet come out on top. Just I'll be damned if the villains own't absurd too. They have to be able to stand to the hero, and have you proverb, 'Man, I don't know if the hero'south going to get in out of this.'"

"If you don't have that," Boseman says, "yous don't have a movie."

This is non just a motion-picture show almost a black superhero; it's very much a black picture. It carries a weight that neither Thor nor Captain America could elevator: serving a black audience that has long gone underrepresented. For and so long, films that depict a reality where whiteness isn't the default accept been ghettoized, marketed largely to audiences of colour as niche entertainment, instead of equally role of the mainstream. Think of Tyler Perry's Madea movies, Malcolm D. Lee's surprise 1999 hit The Best Human or the Barbershop franchise that launched in 2002. But over the past year, the success of films including Go Out and Girls Trip take done fifty-fifty bigger concern at the box part, led to commercial acclaim and minted new stars like Kaluuya and Tiffany Haddish. Those ii hits have only bolstered an argument that has persisted since well before Spike Lee made his debut: black films with blackness themes and black stars can and should be marketed similar whatever other. No 1 talks about Woody Allen and Wes Anderson movies as "white movies" to be marketed but to that audition.

Black Panther marks the biggest move yet in this wave: it'due south both a black film and the newest entrant in the nigh bankable picture franchise in history. For a wary and run a risk-averse film business organisation, led largely past white pic executives who have been historically predisposed to greenlight projects featuring characters who look like them, Black Panther will offer proof that a depiction of a reality of something other than whiteness can make a ton of money.

The film'due south positive reception—as of Feb. 6, the solar day initial reviews surfaced, it had a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes—bodes well for its commercial prospects. Variety predicted that it could threaten the Presidents' Twenty-four hour period weekend tape of $152 1000000, set in 2016 by Deadpool.

Some of the movie's early success tin can be credited to Nate Moore, an African-American executive producer in Marvel's film division who has been song almost the importance of including black characters in the Marvel universe. Just beyond Wakanda, the questions of power and responsibility, it seems, are not just applicable to the characters in Black Panther. Once this motion-picture show blows the doors off, as expected, Hollywood must practise more to reckon with that issue than just greenlight more black stories. Information technology as well needs more Nate Moores.

"I know people [in the amusement industry] are going to see this and aspire to information technology," Boseman says. "Simply this is also having people inside spaces—gatekeeper positions, people who tin open doors and have that idea. How can this be done? How can we exist represented in a way that is aspirational?"

Because Blackness Panther marks such an unprecedented moment that excitement for the motion-picture show feels almost kinetic. Black Panther parties are existence organized, pre- and mail-film soirées for fans new and old. A video of young Atlanta students dancing in their classroom one time they learned they were going to run across the film together went viral in early February. Oscar winner Octavia Spencer announced on her Instagram account that she'll exist in Mississippi when Black Panther opens and that she plans to buy out a theater "in an underserved customs there to ensure that all our brown children can see themselves equally a superhero."

Many civil rights pioneers and other trailblazing forebears accept received lavish cinematic treatments, in films including Malcolm 10, Selma and Hidden Figures. Jackie Robinson fifty-fifty portrayed himself onscreen. Fictional celluloid champions have included Virgil Tibbs, John Shaft and Foxy Brownish. Lando, besides. Only Black Panther matters more, considering he is our best chance for people of every color to run across a black hero. That is its ain kind of power.

Jamil Smith is a announcer born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio. He lives in Los Angeles.

Source: https://time.com/black-panther/

0 Response to "Wakanda Had to Make Up a State Doesnt Exist Black Panther Review"

Post a Comment